LETTERS ON PARAGUAY:

comprising an Account of

a Four Years' Residence

in that Republic, under the Government of the Dictator Francia, by J.P.

and W.P. Robertson. In three volumes, London: John Murray, Albemarle

Street, 1839 (Vol. I second

edition), 1838 (Vol. II).

LETTER I.

To J—— G——, Esq.

General Remarks—Revolt of Spanish America—Colonial Policy

of Spain—Accounts from South America— Lord

Viscount

Beresford—Origin of Enthusiasm about the Country—Reaction. London, 1838

"The numerous works on South America which, within the

last few years,

have issued from the press; the various histories, journals, travels,

and residencies already before the public, have so attenuated the whole

subject, that in writing anything more on it, we are certainly bound to

consider whether we can offer anything new, on topics now so familiar

to almost every class of readers.

We have endeavoured to consider this point; and when we reflect that

the letters which follow, though now edited anew, were substantially

written at the periods to which they refer, and from actual observation

of the facts which they record; if we can add, that they form only a

part of the many documents collected, and of letters written, during a

residence of nearly twenty-five years in Buenos Ayres, Paraguay,

Chile,

and Peru; and if we consider finally, that an intercourse with those

countries has been kept up by us since we left them; we think it will

not be strange if our communications contain something relative to

South America, that has escaped the notice of hurried journalists,

casual visitants, and galloping travellers." (1-2)

"From 1809 till 1822-3, South America

was open, in most

parts, to our commerce; and the information received during that

period, being

chiefly from mercantile men, many of whom had been successful, was

highly

coloured. it not only left, but encouraged parties here to generalize

this

partial success to any extent they pleased. Hence arose an inference of

a

certain universality of wealth; and a prospect dawned upon the minds of

men of

an almost unlimited sphere for the commercial enterprise of Great

Britain.

But it is to Mr. Canning's

foreign

policy, as connected directly with Spain and

Portugal, and through them

with "Spain and the Indies," that the

great bewilderment of this country (for it can be called nothing short

of

that), in regard to South America, is to be attributed.

That ardent statesman already

determined on the vast project of calling

(to use his own words in Parliament) "A NEW WORLD INTO

EXISTENCE,"

sent out diplomatic agents to all parts, to report on the general

circumstances

of that new world.

With the highest deference and

respect for those gentlemen, be it yet

permitted

to state, that tinctured (and how should it have been otherwise?) with

Foreign

Secretary's enthusiasm on so alluring a subject, they went forth

disposed

to report favourably. It was

required also that they should report quickly.

The growing importance of events in the south of Europe demanded this.

The

result was, that the diplomatists, on arrival at the various parts of

South

America, naturally threw themselves on the best-informed merchants for

information. But, beside that it was the interest of those merchants to

magnify

the commercial importance of the country, the very fact of Mr.

Canning's

sending out consuls-general to make treaties of alliance with new

Republics,

fanned in this country the ardent expectations of men already

sufficiently

sanguine. The consequence was, that the reports, although more or less

tinged

with the glow, as well of the great minister who had originated these

measures,

as of his diplomatic agents, and of the merchants by whose assistance

the

documents were framed, were extremely well received at home. The full

recognition by England of many of the Republics followed; and Mr.

Canning,

coming down to Parliament, triumphantly met the fears of those who

dreaded a

continental war, in consequence of the embroiled state of France and

Spain, by

an eloquent speech, in which, if we recollect well, there as a passage

to the

effect that it was long since Spain hat ceased to be formidable in herself: that

it was Spain with the Indies

that had been formidable power; that the Indies

were now lost to her; and that, by recognition of Republics which had de

facto achieved their independence, we had counteracted all

preponderating

influence on the part of the absolute governments of Europe—we had

"called into existence a new world."

This was in the year 1823-4. The

lamentable not to say ruinous results of the

confidence thus established, and of the hopes thus excited, are too

fresh in

the memory of the thousands who have suffered by their connexion with

Spanish

America. Loans were furnished to every one of the independent

governments;

millions were shipped to enable them to work in their mines; emigration

sent

forth her labourers to people the wastes of the new world; manufactures

were

shipped far beyond the amount required for the consumption of the

country; and

we were ere long taught, by a sad experience, that the whole fabric of

these

vast undertakings was reared on a foundation inadequate to support so

great a

superstructure. In 1825 it began to totter; and in 1826-7 it came down

with a

crash which laid many prostrate under its ruins, and more of less

injured

every individual connected with the country. Nor was this, though the

consequence most to be lamented, by any means the only consequence of our overweening

confidence in the infant governments.

Nurtured by these very acts into a

feeling of importance beyond that to which

they were naturally entitled, they have been led too often into a

belief

that

latent views of commercial or more sordid aggrandizement lay hidden

under the

outward show of a liberal and confiding policy; and they have thus not

only

held as less sacred than they ought to have done the obligations they

have

contracted; but they have adopted, in many cases, a narrow and

fluctuating

course of legislation, too much akin to that of Old Spain. Their

injudicious

and ill-timed laws have often hampered commerce, and retarded the

progress of

the public welfare of every section of Spanish America.

Yours, faithfully,

The

Authors." (10-14)

LETTER II.

To J—— G——, Esq.

Was the Declaration of Independence premature?—Solution

of the Query —State of Old Spain — Government of the Colonies —

Military Force of Spain in South America

London, 1838

"It may be asked, and, after what we have said in our last letter, it

naturally will be asked, were

the declarations of independence, then, made by the late Spanish

provinces, premature?

In reply to this question, it may be stated, that if by "premature" be

meant premature in respect of their

moral and political capacity to govern their vast country on sound

principles of political economy, their declarations of

independence certainly appear to involve this charge: for it is a

matter of notoriety, that they are, after more than twenty-five years

of revolution, very little advanced in the science of government, and

nearly as far removed now as they ever wer from political stability.

But if by "premature" be meant only premature in respect to their physical capacity to maintain the independence which they

at first achieved, then it is certain that their

revolution was not premature;

for they have preserved free from all external control, the country

they wrested from hands of Old Spain, till the latter is now

reluctantly forced upon a consideration of the expediency of

recognising the independence of her late colonies, and no longer dreams

of ever repossessing herself of them.

Can it be alleged that upon the whole, then, they have been losers,

rather than gainers by their Revolution? We think quite the reverse.

For one ship that entered their deserted ports, under the colonial

restrictions, twenty now sail into them from all quarters of the globe.

For one newspaper then published, there are now in circulation four or

five. Books of every kind are imported. Foreigners freely take up their

abode in the country. Better houses, better furniture, are seen

everywhere. The natives, guided by the example of foreigners, live not

only better than before, but have acquired habits of greatly-increased

domestic comfort and convenience. In two or three of the republics, the

Protestant religion is tolerated. The undue influence of the priests,

if not entirely undermined, is in many places greatly diminished, and

in

some nearly overthrown. The authority of the pope is not only

practically disavowed, but a legate, sent some time ago from Rome to

Chile, met with a very cold reception, and with an order for his

instantaneous return to that Italy from whence he came. In these, and

in many other respects, the Americans have gained by their Revolution.

They have gained, too, as a consequence of it, in their trade, and

pecuniary transactions with England: for, to say nothing of the large

sums received by them in loans, for working of mines, &c., for

which

little or nothing has been as yet returned; we very much question

whether the merchandise sent to South America has, on the whole,

produced to the shippers of it from this country, an adequate profit;

while it is incontestable that a greatly-increased export trade, at

much enhanced prices, has augmented in all parts of Spanish America the

capital and means of its inhabitants.

What may, however, be truly said of the South Americans is, that they

have not only failed to derive the benefit to have been expected from

their Revolution, under rectitude and prudence of conduct, but hat they

have obstructed such benefit by protracted civil commotions on the one

hand, and by a want of capacity, and sometimes, unfortunately, of

integrity, in the public administration of their affairs, on the other.

Hence, a check to the influx of foreign population, and to the increase

of their own; hence agriculture has languished, and commerce been

shackled by improvident laws; and hence smuggling, that fertile source

of evil, while it has worked out all its demoralizing effects, has at

the same time greatly diminished the revenue. Hence also education has

been neglected, and the vices springing from ignorance left unchecked;

hence factions have been multiplied, and Justice herself has not always

been able to resist the influence of political excitement, and the

temptations to individual venality. Hence, in short, a narrow foreign

policy, and an unhappy domestic one, have too much pervaded the

different states of the ex-colonial possessions of Spain." (15-18)

LETTER IV.

To J—— G——, Esq.

Spanish Population of South America—South American Nobility

—South American Education —the Clergy —the Lawyers —

the Landed Proprietors of Chile and Peru —Estancias,

or Cattle Farms—Estancieros, or Landed Proprietors of Buenos

Ayres—Chacareros, Farmers or Yeomen—General Remarks

"In the first place, it is to be

observed, that those who emigrated from Old Spain to settle in the

colonies, were generally men of neither family, fortune, nor education

at home. Storekeepers from Galicia, small merchants and publicans from

Cataluña, clerks and attorneys from Biscay, and sailors,

drudges, and mechanics from Andalusia, made up the mass of the old

Spanish population. It was only the Viceroy, his staff, and more

immediate dependents, the members of the audiencia, or judges, the

employés of the public offices, and officers of the navy, who

hat any pretensions either to gentlemanlike deportment or tolerable

education. Liberality of feeling, extension of view, or anything

approaching the philosophic and enlightened principle, not having been

taught, even to their betters, in their own country, could not be

imported by them into the new one they adopted. All the natives of Old

Spain were emphatically and indiscriminately denominated by the South

Americans, "Godos," or "Goths."

[...]

For the education of the sons of these different classes of inhabitants

of the Spanish colonies, there were distributed over the continent

several colleges founded by the Jesuits, and universities almost

entirely under the direction of the priests. In Cordoba, there was one

more celebrated university than the rest,—a sort of South

American Salamanca;—in Lima there was another. Cuzco, Chuquisaca, and

Santa Fé de Bogotá were seats of learning of almost equal

note. To these resorted all the youth from the different and far

distant towns and villages of the continent, for such education as the

universities afforded; and they returned to the places of their

nativity, and to their own families, what they were made by the course

of instruction to which in the mean time they had been subjected,

The branches taught were Literae Humaniores,—the theology

of the Roman Catholic church,—the philosophy of the schools,—logic,

upon the strictest models of syllogistic precision, the code of Roman

Law, with all the minutiae of Spanish jurisprudence. The universities

only professed, in fact, to make theologians and lawyers. The

profession of medicine was in the hands of here and there a better sort

of quack from Old Spain, who, mounted on his mule, with a peak saddle

and silver bridle, looked down with disdain upon the crowd of

mulatto practitioners, who drew teeth, let blood, and dealt in simples.

Surgery was almost unknown; and the sciences of chemistry, mathematics,

and natural philosophy, as taught in these enlightened days, were

altogether proscribed. They were considered not as useless merely, but

as dangerous to the state. Not content with having its subjects thus

closely pent up within the confines of ignorance and superstition, the

court readily concurred with the inquisition in framing progressively

enlarged lists, which it was ever issuing, of prohibited books. Locke,

Milton, Montesquieu, and all their heretical followers, it is well

known, were included in those lists; so that knowledge, even with all

the allay of the schools, and all the trash of councils, was literally

weighed out to the Americans in grains and scruples.

[...]

The estanciero, or landed and cattle proprietor, feeling his

inferiority, and taking his station in society accordingly, had his

solace and his recreation in his own solitary avocations, and in the

occasional society of those of his own class, with whom he could

expatiate upon fat herds of cattle,—fine years for pasture,

—horses more fleet than the ostrich or the deer,—the

dexterity of those who could best, from the saddle, throw their noose,

or laso, over the horse of a wild bull,—or of him who could

make the nicest pair of boots from the skin stripped off the legs of a potro, or wild colt.

A good, substantial, roughly-finished house in town, with very little

furniture in it; a large, sleek, fat horse on which to ride;—a

poncho or loose amplitude of camlet stuff, with a hole in the centre of

it for his head and falling from his shoulders over his body;—large

silver spurs, and the head-piece of his bridle heavily overlaid with

the same metal;—a coarse that fastened with black leather

thongs under his chin; —a tinger-box, steel, and flint,

with which to light his cigar; —a knife in his girdle, and

a swarthy page behind him, with the unroasted ribs of a fat cow, for

provision, under his saddle; —constituted the most solid

comfort, and met the most luxurious aspirations of the estanciero, or

Buenos Ayres country gentleman. When, thus equipped and provided, he

could take to the plains, and see a large herd of cattle grazing on one

place, —and in another hear them lowing in the distance;

and when he could look round for uninterrupted miles upon rich

pastures, all his own—his joy was full; his ambition

satisfied; and he was willing at once to forget, and to forego, the

tasteless enjoyments and cumbrous distinctions of artificial society.

Thus lived,—and thus was the country gentleman of the River Plate

educated, before the Revolution. He is now greatly improved in

manners,—fortune,—and mode of life;—and he is rising gradually, but

surely, to that influence to which a greatly increased and increasing

value of property naturally leads." (41-58)

LETTER VI.

To J——

G——, Esq.

NO LONGER INTRODUCTORY.

Retrospective

Glance—Comparison between North and South

America—Plan of the Work—Capture of Buenos Ayres—

Anticipated Results—Consequences of the Capture—Em-

barkation for the River Plate—Arrival there—Bombardment

of Montevideo—Capture of the Town—Symptoms of Con-

fidence in the People—Motley Inhabitants—Expectations

excited

London, 1838

"In

1805-6, news reached England of the expedition to which we have already

referred, under Viscount Beresford, having sailed up the River Plate,

and most valiantly attacked and

taken the town of Buenos Ayres.

The victory, however surprising in itself, was as nothing, compared

with the results anticipated from it by this country. The people were

represented as not only satisfied with their conquerors, but as

tractable, amiable, lively, and engaging. The River Plate, discharging

itself into the sea by a mouth nearly 150 miles wide, and navigable for

2000 miles into the interior of the country, was described as a mighty

inlet to the millions of our commerce. Peru and her mines were held

forth to us as open through this channel: we were told that the

tropical regions of Paraguay were approachable by ships; that thousands

upon thousands of cattle were grazing in the verdant plains; and that

the price of a bullock was four shillings, while that of a horse was

half the sum. The natives, it was said, would give uncounted gold for

our manufactures, while their warehouses were as well stocked with

produce, as their coffers filled with the precious metals. The women

were said to be all beautiful, and the men all handsome, and athletic.

Such was

the description received here of the New Arcadia, of which

Lord Beresford had achieved the most incredible conquest. British

commerce, ever on the wing for foreign lands, soon unfurled

the sails of her floating ships for South America. The rich, the poor,

the needy, the speculative, and the ambitious, all looked to the making

or mending of their fortunes in those favoured regions. Government was

busy equipping, for the extension and security of the newly-acquired

territory, and for the protection of her subjects and their property, a

second expedition, under the command of Sir

Samuel Auchmuty.

Like

other ardent young men, I became anxious to visit a land described

in such glowing colours. I sailed accordingly from Greenock, in

December 1806, in a fine ship called the Enterprise, commanded by

Captain Graham.

The

monotony of a sea-voyage is so well understood, that I shall pass

over mine in very few words. We had the usual winter storms in the

Channel: the ever-paid penalty of a tossing in the Bay of Biscay:

sultry weather in crossing the line, and great rejoicings when, after

three months of pure sea and sky, we got soundings at the mouth of the

River Plate. As we gaily sped our course in now inland waters, and

hoped next day to take up our domicile in Buenos Ayres, we were hailed

by a British ship of war; and alas for the dissipation of the golden

dreams which we had been dreaming all the passage out!

Captain

Graham, having been ordered on board of the frigate, returned

with dismay depicted in his countenance, to tell us that the Spaniards

had regained possession of Buenos Ayres, and made the gallant General

Beresford and his army prisoners.

Our

captain next informed us, that the second expedition, under Sir

Samuel Auchmuty, was now investing Montevideo, and that, with the

exception of the country immediately around the town, there was no

footing for British subjects on the whole continent of Spanish America.

We were ordered to proceed to the roadstead of the besieged city, and

there to place ourselves under the orders of the English admiral.

Down at

one fell swoop tumbled all the castles in the air which had

been built to a fantastic height by the large group of passengers on

board of the Enterprise. Those who had yesterday shaken hands, in

mutual congratulation upon the fortunes they were to make, walked up

and down the deck to-day under evident symptoms of dependency and gloom.

We soon

took our station off Montevideo among hundreds of ships

similarly situated with our own. We were within hearing of the

cannons'

roar, and within sight of the batteries that were pouring their deadly

shot and shell into the houses of the affrighted inhabitants.

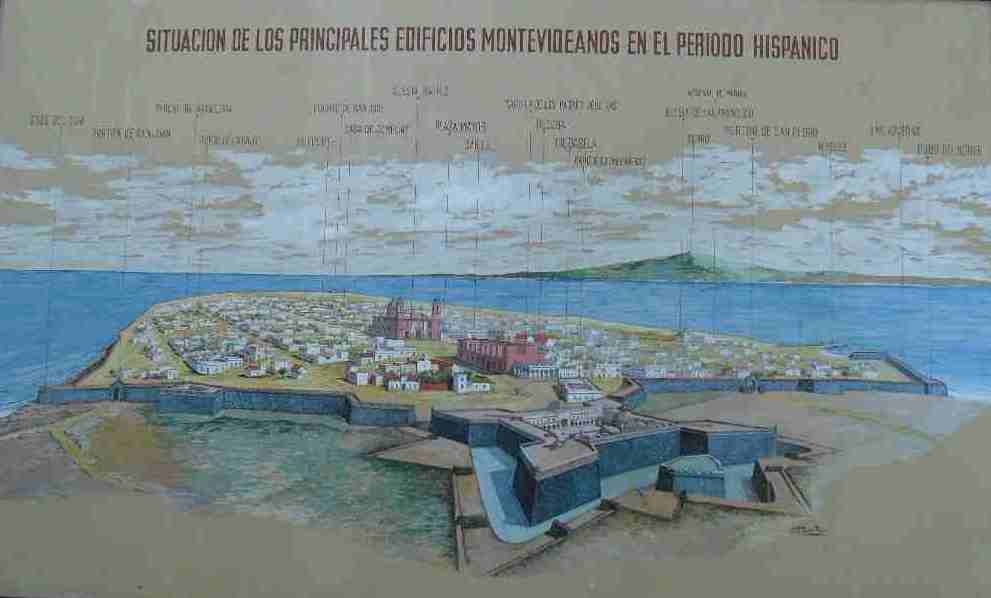

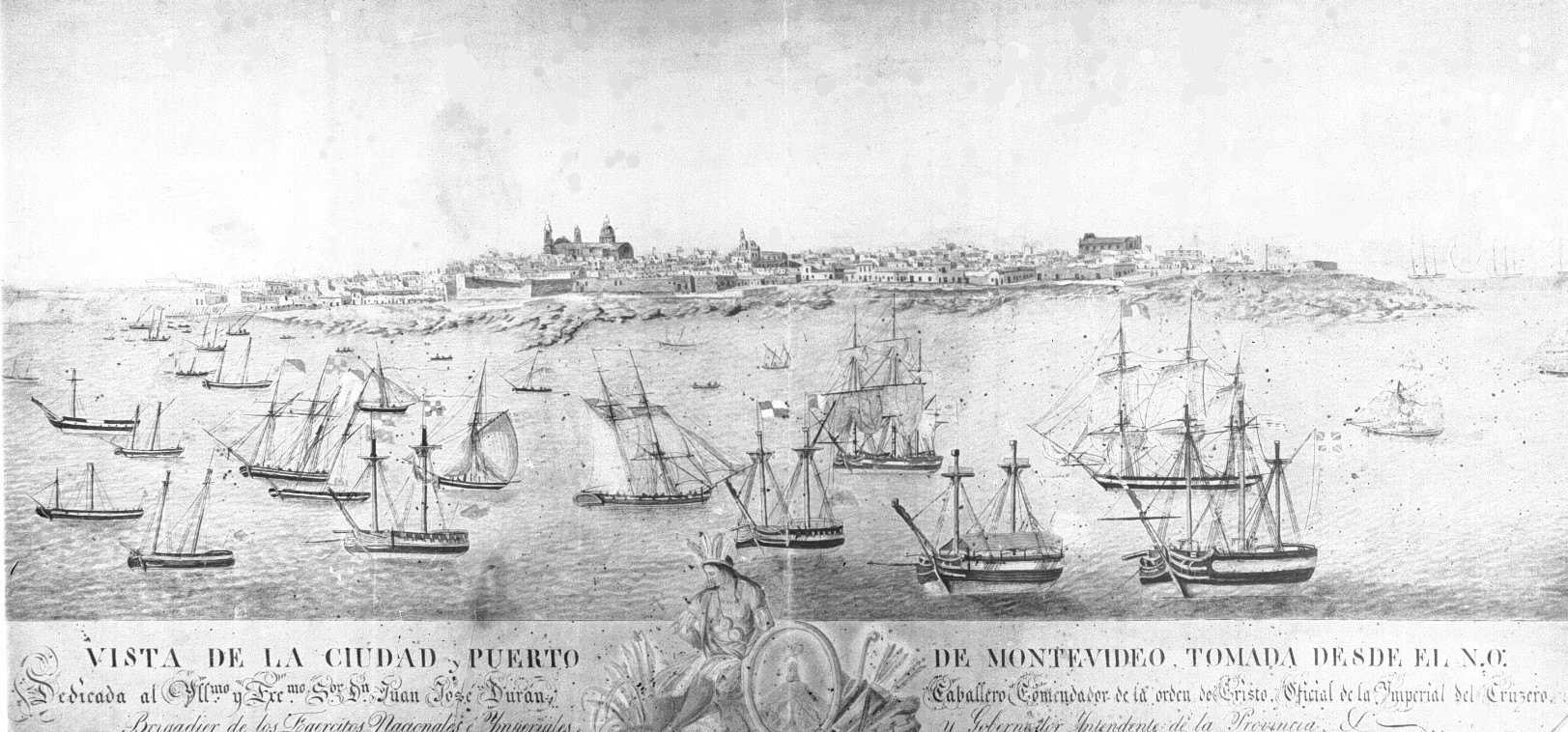

Montevideo

is a town strongly and regularly fortified. In the harbour,

busy boats were to be seen playing from ship to ship; brigs of war were

running close under the walls, and bombarding the citadel from the sea;

the guns were levelled with deadly aim at the part of the fortification

selected for the breach; and the mortar was discharging, in fatal

curve, the destructive bomb. Thousands of spectators from the ships

were tracing, in breathless anxiety, the impression made by every shell

upon the town, and every ball upon the breach. The frequent sorties made by the Spanish troops,

gave an animating, but nervous interest to the scene.

One

morning, at length, before the dawn of day, that part of the wall,

in which was the "imminent deadly breach," was enveloped, as seen from

the shipping, in one mighty spread of conflagration. The roaring of

cannon was incessant, and the atmosphere was one dense mass of smoke

impregnated with the smell of gunpowder. We perceived, by aid of the

night-glass, and of the luminous flashes from the guns, that a deadly

struggle was going forward on the walls. Anon there was an awful pause,

a deep and solemn gloom. The work of carnage was drowing to a close;

and presently the dawn of day exhibited to us the British ensign

unfurled, and proudly floating upon the battlements. A simultaneous

shout of triumph burst from the whole fleet, and thousands who had been

yesterday held in suspense between doubt and fear, gave once more

unbounded scope to a sanguine anticipation of the happy and prosperous

result of their enterprise.

We

landed that day, and found our troops in complete possession of the

place. What a spectacle of desolation and woe presented itself to our

eyes at every step! The carnage had been terrible, in proportion to the

bravery displayed by the Spaniards, and to the gallant, irresistible

daring by which their masses were overwhelmed, and their guns silenced

by the English.

[...]

How all the foreign troops, merchants, and adventurers of every

description got accommodation in the town, it is not easy to say. They

located themselves in every nook and corner of it; so that it soon had

more the appearance of an English colony than of a Spanish settlement.

The number of inhabitants, at the time of its capture, was about ten

thousands: a mixed breed of natives of Old Spain, of the offspring of

these, called creoles, and of a proportionally large mixture of blacks

and mulattoes, mostly slaves. To this population there was an

accession, on the capture of the town, of about six thousand English

subjects, of whom four thousand were military, two thousand merchants,

traders, adventurers; and a dubious crew which could scarcely pass

muster, even under the latter designation.

Hundreds

of British ships were lying in the harbour. Buenos Ayres was

still in possession of the Spaniards; but confident hopes were

entertained that, when it should be heard at home that Montevideo was

taken, a force would be sent out sufficient for the capture of the

capital of so magnificent country. You may guess with what anxiety

we all looked forward to such a consummation; and with what elated hope

we anticipated that the treasures of the towns, and the flocks and

herds of the plains, were soon to come into our possession. We expected

also that in a few months the countries of Chile, Peru, and Paraguay

would be thrown open to our unbounded commerce.

In my

next letter I shall speak more at large of the natives, and

especially of a very admirable part of them,—the women. I

never saw any females more graceful and pretty than they are. One might

apply to almost every one of them the quotation from Milton:

"Grace

was in all her steps, heav'n in her eye,

In ev'ry gesture dignity and love"

Yours, &c.

JPR. (93-103)

LETTER VII.

To J—— G——, Esq.

London, 1838

I had

now, at Montevideo (1807),

entered upon the bustle of active life. During our voyage, I made

myself pretty well master of the principles of the Spanish language;

and my hourly intercourse with the natives of Montevideo, I soon

acquired tolerable fluency in speaking it. As this facility increased,

I naturally drew off from the society of my own countrymen, that I

might commingle more with the Spaniards. Though in an enemy's country,

and a fortified town,—under martial law withal,—hostility

of feeling between the natives and the English was so far subsiding,

that some of the principal families of the place recommenced their

tertulias.

I was

invited to many of these evening parties, and found them an

entertaining mélange

of music, dancing, coffee-drinking, card-playing, laughter, and

conversation. While the young parties were waltzing and courting in the

middle of the room, the old ones, seated in a row, upon what is called

the estrada, were chatting

away with all the esprit and

vivacity of youth. The estrada is a part of the floor raised at one end

of the room, covered with fine straw mats in summer, and with rich and

beautiful skins in winter.

The

gentlemen were grouped in different parts of the room, some at

cards, some talking, others joking with the ladies; while the more

youthful part of them were alternately seated by the piano, in

admiration of the singer, or tripping it on the fantastic toe with very

graceful partners. Every step, and figure, and pirouette, appeared to

me charming. Every lady that I saw in Montevideo, waltzed and moved

through the intricate, yet elegant mazes of the country dance with

grace inimitable, because the result of natural ease and refinement.

Then they were so kind in their endeavours to correct the little

blunders in Spanish of foreigners, without laughing at them, that they

taught by example, at once good feeling, and good manners. There is no

ceremony whatever at the tertulia. Having once got an invitation to the

house ("Señor Don Juan," for instance, "esta es su casa," "this

is your house"), I could visit and leave it at all hours of the day,

and just as it suited myself. At the evening parties which I have

described, persons once invited came in with a simple salutation to the

lady of the house, and departed in the same way." (104-106)

LETTER VIII.

To J—— G——, Esq.

News of General Whitelock's

Expedition—English Militia—Whitelock's arrival—He sails for Buenos

Ayres—Inauspicious March from Ensenada—Panic of the Buenos Ayres

Army—Whitelock's Defeat.

London, 1838

About the time at which

the events recorded in my last letter took place, official accounts

were received from England that a formidable expedition was fitting out

for the River Plate; that General Whitelock [sic] was to be the

commander of it; that its arrival might be looked for in a month; and

that it was immediately to proceed up the river, and take possession of

Buenos Ayres.

When it became known at Montevideo that most of the regular force of

the garrison would be required to co-operate in the intended attack on

the capital, the English merchants and subjects of every description

were called upon to embody themselves into a corps of militia. In the

absence of the greater part of the regular troops, the newly-raised

corps was to keep guard and co-operate with the two battalions of the

line which were to be left to garrison the place.

It was curious,— quite a sight,— to witness the

drilling of this awkward squad of militia.

[...]

At length, Whitelock arrived, with a gorgeous suite of aides-de-camp,

adjutants, commissaries, and other officers of a military

cortège. Sir Samuel Auchmuty was not only superseded in his

command, but eclipsed in his establishment by the now absolute General.

he brought with him eight thousand men, the flower of transports,

protected by noble ships of war. He established a magnificent military

court at the government-house, and magniloquently declared that he

would instantly proceed against Buenos Ayres, and either take or level

it with the ground, within a month from the time of his departure from

Montevideo. We all hoped that the capital might be taken, for we could

not see what we should gain by its being destroyed.

Whitelock ordered three thousand men of the Montevideo garrison to

follow him. Colonel Brown of the 40th regiment was left in command

there; and the merchants were told once more that within a month they

should be at liberty to proceed to Buenos Ayres. The new General hat

the reputation of being a haughty and reserved man; but it was hoped,

notwithstanding, that he would prove himself equal to the fulfilment of

the hight duties to which he had been appointed by the Duke

of York.

Shortly afterwards, General Whitelock sailed with an army of which any

commander might well have been proud, and with a fleet in every well

provisioned and equipped. To the eight thousand men lately arrived,

there were added three thousand of the veteran troops which had taken

Montevideo. Sir Samuel Auchmuty, Colonel Pack, General Gower, General

Crawford, and many other brave and distinguished officers. were under

General Whitelock's command; and as the place had been taken not many

months before by General Beresford with fifteen hundred men, there was

not a shadow of doubt entertained of its at once surrendering to

General Whitelock at the head of eleven thousand.

You may conceive with what exhilarated spirits and elapsed hopes

everybody began to pack up for Buenos Ayres. The ships all bent their

sails; the merchants all gave up their premises in Montevideo; and this

town, like a house when inhabitants are quitting it, had already quite

a comfortless and deserted appearance. For myself, however, I scarcely

knew whether to rejoice at my intended departure, or bewail it.

I was getting so entirely at home at M. Godefroy's, that I began to

fear I might "go farthter and fare worse." I conned over the old and

homely proverb, that "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush;"— which

the Spaniards render, by-the-by, more poetically than we do, by "Mas

vale pajaro en mano, que buytre volando:" "better a little bird in the

hand, than a vulture on the wing."

Shortly after the sailing of the expedition, a brig of war arrived from

the scene of action, and brought intelligence of a landing having been

effected by the British army at Ensenada.

This place is distant from Buenos Ayres about thirty-six miles; and

from it (Ensenada) the formidable force of General Whitelock

immediately began its march. The landing at such a spot struck

everybody, acquainted with the local,

as rather an inauspicious commencement of operations. Military men

said, that in the first place there was no necessity for it; and that a

landing might have been effected as well within five miles as fifty of

Buenos Ayres, seeing there was no regular force that could have impeded

such landing with any hope or chance of success.

In the second place, Ensenada being situated in low, marshy ground,

there were interposed between it and Buenos Ayres immense bogs and

lakes. Through these the army had inevitably to march in order to reach

the capital.

Lastly, no communication could be kept up, on the line of march,

between the naval and land forces; so that the army had to encumber

itself in addition to its heavy baggage and artillery train, with the

immense load of provisions necessary for the subsistence of eleven

thousand men during a march of six or eight days.

At length the expected despatches arrived; and I could scarcely credit

the account which my eyes saw and ears heard, and that now my pen is

constrained to record, of the total defeat of General Whitelock's

expedition. Onward it marched from the ill-fated Ensenada. Lakes,

marshes, hunger, thirst, weariness, cold and fatigue, while they

subjected the gallant army of an infatuated chief to almost every

privation which the human frame could endure, opposed no effectual

barrier against the order to advance. For hours together were the men

up to their middle in water; their provisions were both wet and scanty;

their heavy artillery was often swamped in the marshes; the cold was

intense; shelter there was none; an ill-arranged commissariat left the

men with an insufficient supply of wine and spirits to minister

alleviation to their unprecedented fatigue; the horses on the route of

march were driven away; the cattle too; not an inhabitant was to be

found; and only here and there, at intervals of five to six miles, a

wretched hut, abandoned by its yet more wretched owners, was to

be

seen. Still the British army, led on and encouraged by officers who

might well be classed as the bravest of the brave, hied onward; and in

a few days it arrived within four miles of the destined scene of

operations.

At this time the regular troops and militia of Buenos Ayres marched

out, in the direction of a small river, the Riachuelo, which they

crossed at a bridge called the Puente de

Baracas, that is, the Bridge of Hide-warehouses.

No sooner, however, did those men see the brigades and columns of the

British army, and the train of its artillery moving towards them in

dense and unbroken masses, than they scampered off in precipitate

flight, not only to the town,

but through the town, leaving

it for a whole day literally defenceless. Had the English general marched on, he would have taken Buenos

Ayres without firing a gun or losing a man. A complete panic seem to

have seized the Spanish troops at sight of our

red-coats; and all the efforts of their brave commander, the Viceroy

Liniers, were ineffectual to regulate their retreat, or, more

properly speaking, to stay their flight.

But General Whitelock did not

march on: he made an ominous, a most unintelligible, and ruinous halt;

and to this halt, not less than to his subsequent mode of attack upon

the town, is to be attributed the defeat of his brave army; the loss of

nearly three thousand of the most intrepid of his men; the abandonment

of Buenos Ayres; the restitution to Spain of Montevideo; and such

disgrace to gallant soldiers, as could only have been brought upon them

by a general the most inert, self-willed, capricious,—combined, withal,

the apparently opposite qualities of rashness and cowardice,—that ever

took the field.

When Colonel Brown communicated to the English residents at Montevideo

the disastrous results of General Whitelock's short campaign, a tear

stood in his manly eye; and when he informed us that the capitulation

by which the English army was to be "permitted" to evacuate Buenos

Ayres, contained also a clause for the abandonment, within two months,

of Montevideo, the soldier could proceed no farther. He quitted, in the

greatest agitation, the room in which he had been compelled to announce

at once the defeat and humiliation of the brave army of which he was

himself one of the brightest ornaments.

In my next letter, you shall have a few of the details by which this

unlooked-for catastrophe was brought upon us; sending us all, as a

necessary result, to that point which, when our countrymen have once

left home, they so generally dislike,— "back again."

Yours, &c.

J.P.R." (113-123)

LETTER IX.

To J—— G——, Esq.

Causes of the

defeat at Buenos Ayres—The Capitulation—General

Whitelock's callousness—Departure of the English from the

Country—Transition from Land to Sea—Reflections.

London, 1838

"Buenos Ayres is a very large town, of which the streets

intersect each other at right angles, some of them being more than

three miles long, in a straight line.

The

British general ordered his columns to advance along those streets,

to given points of junction and rendezvous, and without firing a shot at the

people on the house-tops, or elsewhere. The flints were in some cases

taken out of the soldiers' muskets,

You need

hardly be told what followed. The brave troops, disciplined to

strict obedience marched along those pathways of death, without

offering the slightest resistance. The ranks were thinned by the

sharpshooters from the azoteas, or house-tops, with such fatal

rapidity, that not only were the streets, at every step they took,

strewed with slain and wounded, but when they hat in some instances

attained, and in others nearly so, their appointed places of

rendezvous, they were so reduced, by the incessant firing upon them

from the house-tops, as to be obliged to take shelter in the nearest

churches or convents. Still, General Whitelock hat a corps of reserve

of five thousand men, who hat not yet come into action; and with them

he might, even at the eleventh hour, have achieved the work of

conquest. But, panic-struck by the death, desolation, and confusion to

which his own wretched plan of operation had inevitable led, he lost

all self-possession, energy, and courage. He capitulated,—on

condition of being allowed to retire with his yet but half-vanquished

army; and he agreed not only to abandon all farther attack on Buenos

Ayres, but to sail within two months, with his whole force, from the

River Plate. "Put in," said Alzaga,

the Alcalde de primer voto, or mayor, who was a party to the drawing up

of the terms of capitulation, "put in, that he shall also evacuate

Montevideo." "Oh," said the viceroy, Liniers, "that is out of question;

it would spoil the whole matter." "Let

us put it down," replied the resolute and influential citizen;

"it can be easily taken out, if objected to." It was put down, and it was not objected to. The bewildered

Whitelock conceded all; and in a few days afterwards we

beheld to our dismay, in Montevideo, the transports and ships of war,

which, one little month before, had conveyed our noble army to

anticipated triumph, returning with that army defeated, and its general

irretrievable disgraced. The hospitals were once more filled with the

sick, wounded, and dying. Three thousand gallant fellows had attested

by their death their dauntless courage in the streets of Buenos Ayres;

and yet General Whitelock— himself the sole cause of the

unpardonable catastrophe—strutted on the azotea of the

government house, or rode through the streets of Montevideo, the only

unconcerned individual, to all appearance, in the midst of the shame

and disgrace which he had brought upon the arms of Great Britain.

To have

seen him at the moment when the garrison was about to be delivered up

to General

Elio, you might have supposed him, from his air, a Willington or a

Wolfe. It was impossible, from any outward demonstration, to fancy him

a man conscious of the appalling and criminal loss of life which his

dogged stupidity had brought upon an army which, under better

management, might have conquered and kept one-half of the New World.

With the outmost unconcern, he saw us quit a soil which, but for his

folly and madness, might have been ours for generations yet unborn

What was

greatly to be admire, in this terrible reverse, was the unassuming

deportment, indeed the increased deference, of the Spaniards towards

the English. They never alluded to the subject of Whitelock's defeat;

and when they spoke of our departure, it was ever with an expression of

regret that they were about to lose many personal friends. Such conduct

I could not but think very demonstrative of courtesy and good feeling;

magnanimous almost in a people now triumphant over their recent

invaders.

In

lingered in the town till the last moment, and then, with a heavy

heart, bade adieu to M. Godefroy and his family. The parting was

more like that of a son from father and mother, and of a brother

from sisters, than of a foreigner and an enemy from people whose

acquaintance he had not enjoyed above five months.

I had

the mortification, too, to see the Spanish colours flying on the

citadel, and at the government house. Elio and his staff had already

received the key of that place; the last English stragglers were

hurrying to their boats; and in a few days the whole fleet, consisting

of two hundred and fifty ships, sailed out of the River Plate.

The disastrous manner in which we were thus driven from the country

was, as you may conceive, the more keenly felt that such a result was

not only unexpected, but the very reverse of what even the least

sanguine calculation had anticipated.

[...]

Yet, in alleviation of these more sombre musing, it was cheering to

reflect that whatever may be the causes of quarrel, and whatsoever the

ravages of war, between nation and nation, they cannot stop that

current of the milk of human kindness which circulates, in greater or

less abundance, in the breast of every individual of the family of man.

Endued with the same nature, created with the same propensities,

influenced by like motives, and animated by like passions, man

everywhere recognises man; the general principles of humanity are

developed in all the various circumstances in which he is placed; while

in all the different climes which he inhabits, under every modification

of national character, still a feeling common to humanity prevails.

So to

me, a protestant, the right hand of fellowship had been held out by a

catholic; one of a nation of invaders, I was individually cherished as

a friend by those invaded; far distant from my own family, I was

received in Montevideo into the bosom of many families to whom, a few

months before, I had been totally unknown; and my youth and

inexperience, which, in another country, might have exposed me to

worldly artifice and trickery, were there my best passports to pleasing

society. They were my chief claim to hospitality and kindness.

I was

truly glad when we sailed into Kinsale harbour, after a tedious passage

of fourteen weeks, during four of which we had been on short allowance

of provisions and water.

That

nothing might be wanting to complete the mistakes of the

disastrous River Plate expedition, the transports had taken in their

water too near the mouth of the river; so that it was brackish and

putrid, long before the fleet reached Ireland; and the use of it had

caused the death, from dysentery, of many of the troops.

Yours, &c.

J.P.R."

(126-133)

LETTER XL.

To J—— G——, Esq.

Dismemberment of the

Provinces of Rio

de la Plata—General Artigas—Journey to Santa Fé—The Major of

Blandengues—Thistles—Journey continued—Arrival at Santa

Fé—Artigueños—Smoking—More of Candioti.

London, 1838

"The dismemberment of

the

provinces of Rio de la Plata as constituted by Old Spain, began with

Paraguay. But that territory could at no time be said to have formed a

portion of the "United

Provinces," as created by the patriots. It never gave in its

adhesion to them, but established, on the ruins of the power of Spain,

an independent government of its own.

The first great intestine feud was raised by General

Artigas, the most extraordinary man, after Francia, that figures in

the annals of the republic of River Plate.

Artigas came of a respectable family; but was, in

his

habits, only a better sort of Gaucho, of the Banda Oriental. He was

wholly uneducated, and, if I mistake not, learned only at a late period

of his life, to read and write. But he was bold, sagacious, daring,

restless, and unprincipled. In all athletic exercises, and in every

Gaucho acquirement, he stood unrivalled, and commanded at once the fear

and the admiration of the surrounding country population. He acquired

an immense influence over the Gauchos; and his turbulent spirit,

disdaining the peaceful labours of the field, drew about him a number

of the most desperate and resolute of those men, of whom he assumed the

lead, and in command of whom he took to the trade of a contrabandista,

or smuggler.

He would march with his band by the most rugged roads, and through

apparently impenetrable woods, into the adjoining territory of Brazil,

and thence bring his contraband goods and stolen herds, to dispose of

them in the Banda Oriental. This was under the rule of Old Spain. Every

effort of the Governor of Montevideo to ut the bold smuggler and his

band down, was not only unavailing, but always ended in the defeat of

the forces sent against him. The country even then belonged to Artigas.

He would meet, engage, and rout the king's troops; till at length, his

very name carried terror with it. But he was strict disciplinarian;

respected the property of those who did not interfere with him, and

only attacked those who presumed, or dared to throw impediments in the

way of his illegal traffic. He was the Robin Hood of South America.

The governor of Montevideo finding Artiga's power constantly on the

increase, at length sought his friendship in the king's name. Artigas,

tired of his marauding life, listened to the overtures made to him. A

treaty was formed; and, as a consequence of it, he rode into Montevideo

with the king's commission of Captain of Blandengues, or mounted

militia of the country. His band of contrabandistas became his

soldiers;

and he thenceforward kept the whole country districts of the province

in an order and tranquillity which they had seldom before enjoyed.

In this situation did the revolution in Buenos Ayres find Artigas; and

in 1811 or 1812, he deserted from the king's service in the Banda

Oriental, and joined the patriots. He was considered to be a great

accession to the cause; and when Montevideo in 1813 was besieged by

Buenos Ayres force, under the command of General

Alvear, Artigas served under him with the rank of Colonel.

A new and wider field now opened itself up to the view of this

ambitious and unprincipled chief. His haughty and overbearing spirit

could no longer brook an inferior command under a Buenos Ayres General,

and in the face of his own paysanos,

on whom, since the King of Spain's authority was disputed, he began to

look as his own legitimate subjects. Besides, the more polished and

civilized of the Buenos Ayres chiefs looked down upon him as on a

semi-barbarian, and treated him without the respect which he considered

due to his rank. So he hated them all. He tampered with the troops

under his command. They were all Orientales [Natives of the province of

Montevideo, called the Banda Oriental,

or East side (of the Plata)], and adhered to him to a man. He laid his

plan with his usual sagacity: he silently abandoned the siege during a

dark night, with his eight hundred men; and whe it was reported to

General Alvear in the morning, Artigas was many leagues off with what

he now called "his army." This was at the close of 1813." (179-182)

Last update: November 30, 2019

|